Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe to podcast: Apple Podcasts |

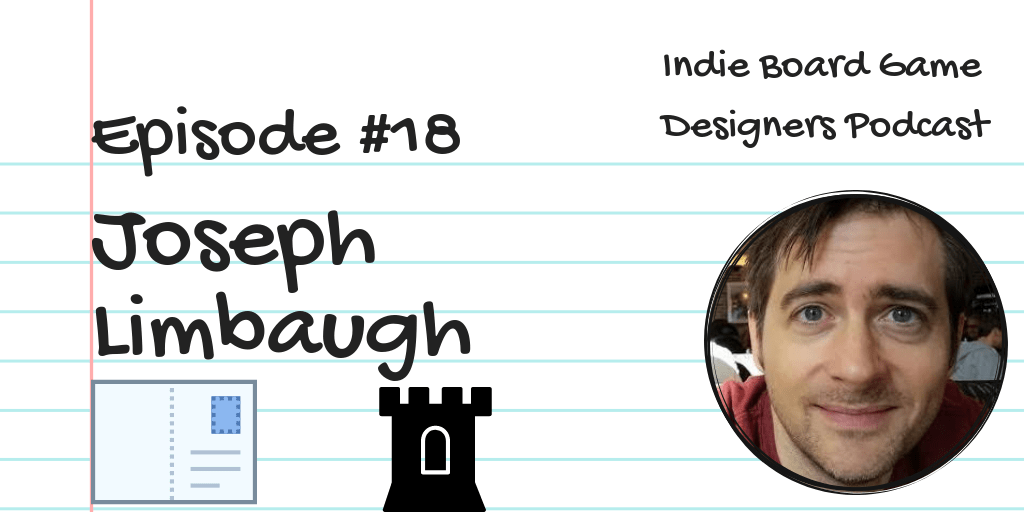

Patrick Rauland: Hello, everyone. Welcome to the Indie Board Game Designers Podcast. Today we're going to be talking with Joseph Limbaugh, who is the designer behind Postcard Dungeons, which is a game you can play out of a postcard. Joseph, welcome to the show.

Joseph Limbaugh: Hello, thanks for having me, Patrick.

How Did You Get Into Board Games?

Patrick Rauland: First of all, thanks for being on here, I'm really happy you're on the show. How did you, number one question I ask everyone, how did you get into board games and in board game design?

Joseph Limbaugh: Wow. I started pretty early, I think, as many people did. I started off, I think, mostly with role-playing games, because it's like, I kind of started all this in the 80s, when I was quite young. Role-playing games is where I got started. Then, there's a lot of board games back then, and kind of branched out from there. I think, I remember, some of the earliest games playing Divine Right, I don't know if you've heard of that game.

Patrick Rauland: No.

Joseph Limbaugh: That's like an old school war game, because back then most board games were called war games, because it was mostly like war simulations, and things like that. But I was always kind of a little bit more interested in role-playing games than board games back then. Yeah, that's pretty much when it happened. I'm from Portland, Oregon, I would go to a place, there was a Western Oregon Board Gamers Club. Maybe is Western Oregon War Gamers, but it was a bunch of old grognards, and they would play. They did Dungeons & Dragons, but they also did all the Napoleonics and all the old school miniatures games. They played all that stuff, Chivalry and that sort of thing.

Patrick Rauland: For people who are not familiar with that vocabulary, what is a grognard?

Joseph Limbaugh: A grognard is, supposedly it's what Napoleon called his generals, it means I think “grumbler” in French. They were his old really experienced generals who would be like, “No, this is a bad idea. Or this isn't going to work.” But he would sought advice from them. But then, when Napoleonics was kind of where Dungeons & Dragons and a bunch of those miniature games out of that … they called the people who played those games, grognards, that was kind of a nickname for those people. They're like older, 30, 40-year-old people who had a bunch of miniatures in their basement.

Patrick Rauland: Okay. I love war games, I play Warhammer. What age range, or whatever do I become a grognard? Like is it … because I'm in my 30s now, am I already a grognard or do I need like a beard at 30, or how does it work?

Joseph Limbaugh: I think yeah, you've got to be at least middle age to be a grognard, I would say. Yeah.

Patrick Rauland: So, it's 40 or I don't know when middle age starts.

Joseph Limbaugh: Probably … yeah, I think 40 is generally what people say is the beginning of middle age. But if you're playing with young people, then you're a grognard.

Patrick Rauland: Oh, no. If I play with the young 20-year-olds and I'm the 30, I'm the grognard?

Joseph Limbaugh: Yeah, for sure.

Where Did The Postcard Come From?

Patrick Rauland: All right, it's already happened, it's too late. Okay, let's end this interview. We are done. I am depressed. No. You designed a game that is the size of a postcard. How did you decide? Where did that idea come from?

Joseph Limbaugh: I've actually designed several games on postcards. It's kind of a combination of things. Once again, when I was younger, there was a magazine called Dragon magazine, that was kind of a Dungeons & Dragons, like the original Dungeons & Dragons magazine. There would be games occasionally in that magazine, you could pull them out of the magazine, and cut out the pieces, and play the games. I just always loved the idea of a small space, fitting that game into a small space and the design challenge of that. Then, I've always kind of dabbled in designing games. But as you know, recently, this whole industry has just like blossomed, it's huge with Kickstarter and everything. Some friends of mine did kickstarters, and I watched, I was very interested in it, I was like, “Oh, maybe I can actually design a game and people might want it.”

Joseph Limbaugh: But I also realized like reading all the stories of people on Kickstarter, so many people really did not, it was very hard to, especially fulfillment, like sending the game out was the hardest part, also like sourcing people who make dice, and all the different components. It is a tremendous challenge to fulfill a kickstarter if you're not a game company. At the time, I was doing a lot of improvised shows, and we would always make postcards for the shows, we've had our special art made for the postcards. I always liked the feel of a postcard. I was like, “You know what? I could get these printed up and put a game on them. I could design a game and put it on here.” That would be like I could put a whole game.

Joseph Limbaugh: Originally, it was just like a marketing idea. Because a friend of mine Eliot Hochberg and I have kind of a game design collective called Modest Games. I'm like, We can make some games on postcards and just give them out to people.” And be like, “Here, I just gave you a game on this postcard.” It's kind of the short version of the long story, but it was still long.

How Did You Succeed On Kickstarter?

Patrick Rauland: No, I think that's a really cool story, and I love the idea of small and portable in a postcard. You could put it in your back pocket. I wouldn't, because I don't want it to be bent. But you could fit it in your back pocket, which is really, really cool. Now, your game, you raised quite a bit of money in Kickstarter, I think, because your base pledge is $4. I can't think of a game that had a small, excluding digital files or whatever, I can't think of a game that had a lower-based pledge. I think you had over 3000 people buy your game. That's something like $30,000. Most kickstarters don't get that high, and your base pledge is $4. What do you think it was about your game that connected with over 3000 people?

Joseph Limbaugh: Honestly, Patrick, I'm not 100% sure, I do think the low price point was a valid metric. When I put the kickstarter up, my goal was $1000. The game was finished and I didn't have like a really, I think, a very good description of it, but still people were just like, “It's $4, I'll go ahead and … I'll go in on that.” It's hard for me to say exactly why it was … I'm really grateful that was, I was so excited and amazed by it. I'm don't totally know for sure. I also think, I put it up at a time when there wasn't a lot going on in Kickstarter, there's kind of like known wisdom of Kickstarter is to put your game up at certain times. I did it I think in December, which was, no one puts games up on December, because everybody is spending their money on Christmas, or Holiday times.

Joseph Limbaugh: But, my game is like $4, so I'm like, “People will still have $4 to spend, to do it.” I don't know, that might've had something to do with it.

Were There Component Limitations?

Patrick Rauland: Yeah. I think it's really, really cool. Whatever the magical reason is, I think it's really cool. Because your game is so small, you obviously had really tight restrictions, you're very limited in space and components, which [inaudible 00:07:46], or bring your own components, I should say. Was there something, there have to have been things you wanted to add to the game, but you just couldn't because of space, right?

Joseph Limbaugh: Yes. I think the challenge with any game is getting rid of things that don't help the game player, don't streamline it, or are not fun. I think that in game design, you have to reach a point where you're like, “I got to cut this stuff off.” But with a postcard game it's even more. You really have to, you know. The game went through significant changes as I cleaned it up and streamlined things. You could literally spend forever fixing a game, and trying to get it perfect. I try to make my games to be good games as much as possible, but I try to avoid making them perfect, because I think you will never finish your game if you do that. You'll never be done. Also, everything with Postcard Dungeons is, I didn't originally have any stretch goals, but since it started taking off, I was like, “Oh, I got to make some stretch goals.” Because I feel like I should give people something for all the support of my game.

Joseph Limbaugh: We created some stretch goals, so I think like most of the stuff that I kind of wanted to add to the game I was able to add as an expansion postcards that people will get as I send them out. There's like a Megadungeon expansion, there's a Co-op version, which is quite different and was pretty challenge to create, like a Player's Compendium, so you can play as different races and classes, stuff like that.

Patrick Rauland: Yeah. Something else that must have been challenging is when you encourage players to bring their own components, you're obviously pretty limited, right? You can't be like, “Bring out your D77.” I don't have one of those. I'm curious about components, how did you decide what compo- … correct me if I'm wrong, it's just dice, right? Or is it other things too?

Joseph Limbaugh: It is D6s, and tokens, you have to have some tokens, each player needs four tokens that represent them.

Patrick Rauland: Right. Okay. [crosstalk 00:10:01].

Joseph Limbaugh: My previous game, it's for Postcard Empire, and Postcard Cthulhu, the whole idea was you need coins to play them, because we figured everybody would have coins with them at any given time. This was kind of a bit of an experience, because I didn't know like, “Would people want a game if they were supplying the dice and the tokens? Would they be interested in that? Would they support it?” Apparently the answer is yes. I do definitely put a lot of thought to like what will people reasonably have. I wouldn't ask for people to have polyhedral dice for the game. I feel like that might be a big much. I've also like, “How many dice could I reasonably expect people to have?” You need seven dice to play the game, and then four tokens for each player, which I think is … I don't know, I don't know, I could probably push it a lot farther, but to me it's … I also like the challenge of trying to make a game as simple as possible, but still have it have some compelling gameplay. It's kind of a feature, I think, not having enough components.

Patrick Rauland: Yeah, I find that fascinating, because it's funny I have so many dice in this house, but they're all in specific games. I play Warhammer, and I have multiple armies, I've like these green dice are only for my orcs, and these yellow dice are only for this army. I'm really specific. When someone asks me to bring out dice, I'm like, “Oh man. [inaudible 00:11:28] I forget to put them back and I lose all my green dice. I wouldn't be able to play as my orcs anymore.” I get really OCD, I don't know if that's the right phrase there, but it's just an interesting decision to like asking people to bring their own components. I think you did the right thing of not asking them to bring only D6s is probably the best, is probably the easiest thing to do.

Joseph Limbaugh: Yeah. Even if you have like muggle board games like Monopoly or whatever, it's like-

Patrick Rauland: Muggle.

Joseph Limbaugh: You know what I mean. If you have those, you have some six-sided dice. I think you can rustle up, or Yahtzee, it's like, you can rustle up six-sided dice without an issue.

Are You Going All Into The Postcard Format?

Patrick Rauland: Yeah. You've already created three postcard games, this is your third. Do you want to keep designing these games? Or you've been like, “Postcards are my thing, I love the post.” Or are you going to start trying other formats?

Joseph Limbaugh: I do have other formats, and I have actually designed some other games, but I do … I have at least two more postcard games that I have designed, that I'm going to see how they go, I'm going to kickstart both of them and see how they go. Because I like the format, and I enjoy designing for the format. If people continue to like them, then yeah, I'm going to keep doing that. At some point I will definitely want to produce another type of game, but I don't know if I … I like postcard games, yeah, I'm following up on that for now is the plan.

Which Game Design is Your Favorite?

Patrick Rauland: Got it. Of the games you've designed so far, which one is your favorite?

Joseph Limbaugh: I think probably it would be Postcard Dungeons, honestly, but it's a close call, because there's another, there's a card game that you can download as a print and play called Thieves, that's also another dungeon-themed game. But it's like a group of thieves. If you went on like a dungeon crawl and everybody in the party was a thief, it's all about kind of backstabbing the other players and lying to them. But yeah, I think that or Postcard Dungeons. I'm really proud of Postcard Dungeons. The other postcard games, I did not kickstart those games, because although I like them, I feel like, I don't know, they're still not like, they could be better. I feel like they could've been better. Just like the challenge of designing in that space is very tricky. I don't know, but Postcard Dungeons I think, yeah, it's my favorite game currently that I've done. Yeah.

Patrick Rauland: I'm a little bit lost, because I'm thinking about a party full of only thieves, and how like you enter the dungeon. Everyone hides in the shadows, and you're like, “Well, all right.” I can imagine everyone in one shadow in the corner of the room.

Joseph Limbaugh: Actually, you have the option every turn to either hide into the shadows or to stab someone in the back, or to try to steal something. Then, it's kind of a rock paper scissors mechanic, depending on what other people do, you succeed. Then one of the thieves, every turn, is the scout, and they go ahead and they scout ahead to see what's in the room that's coming up. Then they come back and tell everybody. But of course, they're probably lying about that. Whatever they tell you about what is in the room is designed to mess with everybody else.

Patrick Rauland: This sounds great.

Joseph Limbaugh: It's a good game. I'm really proud of that one. It's funny because Eliot and I, Eliot Hochberg, when we started Modest Games, we had this, we were like, “We're going to design a game every week.” That was our thing. [inaudible 00:15:07], “Each week we're going to bring a game, and we're going to design a game.” Was our challenge. That was the first game I designed. Then I just kind of spent … We didn't design any more games weekly after that, because I spent all the time tweaking Thieves, because I was really excited about how it turned out.

What is Your Game Design Process

Patrick Rauland: What is your game process like? How do you get to a game like Thieves or Postcard Dungeons?

Joseph Limbaugh: I usually will come at it from a theme point of view. I think, those kind of the two things are either you come up with a cool mechanic, and then you think of the theme around it, or you come up with the team, and then you kind of figure out the mechanics. I do like starting with the theme first, because I feel like for me it inspires interesting mechanics. How can you simulate this idea of a bunch of thieves going into a dungeon there not being any other classes there? In fact, I have some other games in that series that I'm working on.

Joseph Limbaugh: The fighters, or warriors, is a game. Where it's like a party of all warriors, but the idea for that is that it's all about them bragging about what they could do. It's like, “I can fight this monster with my arm tied behind my back.” It's like, “I can fight the monster with the arm tied behind my back, and with my eyes closed.” It's like, “Oh, you go fight that monster then.” It's like, that is inspirational of like how do you come up with mechanics for have that to work.

Patrick Rauland: That sounds really great. All right, now I need to somehow pitch you to the [inaudible 00:16:42] for Mages, where we just read books together, I don't know.

Joseph Limbaugh: Mages was all about … I think the idea I had for that, it was all about complicated spells. Metaphysical big words, and creating super complicated spells.

Patrick Rauland: There could be like a memory components to that game. You can literally cast whatever spell you want, as long as you remember what the secret word is, or something.

Joseph Limbaugh: Like you have to literally memorize spells. The [inaudible 00:17:09] in magic would be taking to the extreme of like can you actually remember this?

Patrick Rauland: I think this is accurate, but this doesn't sound fun.

Joseph Limbaugh: That is … yeah, that's the challenge, it's making it fun. Yeah.

What Game Would You Like To Change?

Patrick Rauland: Okay. Wow, we just covered a lot of these questions. Is there a game out there that you wish you could change maybe a game made by someone else? Maybe you can want to add something, or take something away from it.

Joseph Limbaugh: That's … I marked this question?

Patrick Rauland: You did. You said this would be a question you'd like to answer.

Joseph Limbaugh: A game that I would want to change. I don't remember what I thought the answer would be.

Patrick Rauland: The other way of me phrasing this question is, is there maybe a game where you're like, “Man, either this feature should be an expansion,” or you're like, “This game is great, and it needs an expansion.”

Joseph Limbaugh: Maybe, and we're talking about just games out there in the world, right?

Patrick Rauland: Yeah.

Joseph Limbaugh: I think like Arkham Horror, I would say I would want it to be more like streamlined. But I think they kind of already did that with Eldritch Horror, you know what I mean? Because I'm a huge Lovecraft fan, I have a ton of, I have all the role-playing games of, you know, Call of Cthulhu, and Delta Green. And I love that game, but it's like, yeah, it's a long slog, and it could really be streamlined. But it's already been done, they did with Eldritch Horror.

Patrick Rauland: Correct me if I'm wrong, isn't all the H.P. Lovecraft stuff in the public domain?

Joseph Limbaugh: I believe so. I think it's a little bit of a tricky legal thing, but for the most part, yes. It's in the public domain in like everywhere else in the world, but America, because of Disney, and Disney kept lobbying to have the copyrighting increased, whatever. I think it's a little bit of a gray area here. But it's also like there's no … Because, Arkham House, I think was publishing his stuff … I don't know, it's … no one's really challenged this. I think everybody creates Cthulhu stuff, and no one is like fighting to [crosstalk 00:19:23] them not do that, but it is.

Patrick Rauland: Okay.

Joseph Limbaugh: That's my understanding. I'm not a lawyer. I'm not a lawyer, Patrick.

Patrick Rauland: The real question I wanted to ask you is when is your game, when is your Call of Cthulhu game coming out?

Joseph Limbaugh: Postcard Cthulhu is already out, you can buy it on the website.

Patrick Rauland: Great. That was one of the other ones. Awesome.

Joseph Limbaugh: Yeah. One of the games, I'm doing another Cthulhu game, which is one of the two Postcard games is a Cthulhu-themed game. Probably won't be the next one that I kickstart, but the one after will be that. Because I love Postcard Cthulhu, that my artist did an amazing job, Kristen Immoor, it is a good game. It is also pretty fiddly, because I literally, I tried to put so much into that one postcard that it's a bit fiddly. There's a video tutorial you can watch to play it, but yeah, it's a tricky to game to kind of wrap your head around, because I really, really shoved The Kitchen Sink and the Elder Gods into that postcard.

What Resource Do You Recommend?

Patrick Rauland: What one resource would you recommend? I like to assume that most of the people listening to this are an aspiring designer, or they've maybe got their first game signed. What would you recommend to someone to get them on the right track?

Joseph Limbaugh: I spent a lot of time on Stonemaier Games website, like their blog. I'm sure you've … especially for Kickstarter. It's literally, for me it was like a how to manual of Kickstarter, if there was one. You can go there and type in, what's going on? How does international mailing work? And it's like, “Oh, here's a ton of information about that specific topic.” If it's Kickstarter related, I would say that … as far as like game design in general, I think just play more games, open yourself up to some different ideas, and find … there's game testing and playing groups near you, find one and start interacting with other people I think. Because getting feedback from other people on your game designs is so important, especially if they're friends of yours and will be completely honest and they have good insight. You know what I mean?

Joseph Limbaugh: Like my friend Eliot, and [inaudible 00:21:46] is our other friend when we first started. I always want them to play my game and then tell me stuff, because they always have such great feedback. That's invaluable, it's invaluable.

What is your Community Like?

Patrick Rauland: Yeah. I like to ask people about their local communities, because it seems like some communities are on fire, and they have multiple game design meet ups every week. Other communities are like, “We have one thing once a month if someone shows up.” I'm curious, you're in LA, right? What is the community there like?

Joseph Limbaugh: There's a ton of stuff. I generally, I've been doing stuff with First Play: L.A., which is like a board game design collective, and everyone over there is super awesome. I mean, there's also Strategicon, which is like, it is a game con that happens three times a year. It's down by the airport … I've met a lot of people down there, it's a huge city, and there's tons of stuff happening. That's just even scratching the surface. There's plenty of other stuff that I could be doing, that I probably should be doing. Yeah, there's a lot of stuff here, you can-

Patrick Rauland: Yeah. What is a fun idea, a theme, or a mechanism that you are looking into for a future game?

Joseph Limbaugh: I'm a big fan of interactive storytelling. Because I'm also an improviser. As an improvisational performer, I love creating stories in real time, to me that's what I love about it. I like making people laugh, but to me creating a narrative is the exciting part. A few years back, I was kind of just looking around the web, and I found this guy called Chris Crawford. He used to design games for the Atari 2600. He's like this old school video game developer from the '80s. He's really, really smart guy. He's also a super, he's like an curmudgeonly dude.

Patrick Rauland: A grognard.

Joseph Limbaugh: He is a grognard. With some strong opinions, but he founded the Game Developers Conference. Then he left because of political and money issues kind of took it over. His Holy Grail is to creative interactive storytelling on the computer. He has algorithms he's written, and ideas about that would work. To me, I find it very fascinating. I think there are like board games that are doing that now, where there's like narrative hard-baked into the rules of the game. Dead of Winter is an example, I think Robinson Crusoe has some of that stuff. More recently, I think the new Fallout game some stuff like that.

Joseph Limbaugh: I just love the idea … Arkham Horror is the same way, it's kind of like the game is the game master for the players. What am I thinking of? What's the … I shouldn't remember. You know what I'm talking about. It's like this huge game, it's like a role-playing game, it has … it's not shadow something, twilight-

Patrick Rauland: Shadowrun?

Joseph Limbaugh: No, no, no. It's a board game, that everybody plays, and I've played it, but for some reason-

Patrick Rauland: Gloomhaven?

Joseph Limbaugh: That's it, Gloomhaven. Oh my gosh.

Patrick Rauland: Gloom, shadow, I get it. Yeah.

Joseph Limbaugh: Gloom-shadow-haven fall town, yeah, but like Gloomhaven is like once again, it's like the kind of the role-playing elements and the story elements are baked into the … to me, there's a game I've been working on that's a card game that uses that, but it's more kind of story oriented than goal oriented. I think so. That excites me.

Patrick Rauland: I [inaudible 00:25:46], I just want to go back and cut you on Gloomhaven, because I don't have the game, I really wanted to play, because it's like number one on BGG, or at least it was, I think it still is. I really wanted to play it. A friend of mine, he's like, they've may be 25% of the way through the game, and I asked him to come over, and I got to play, I didn't feel like there was any story at all, because it's like, “All right, cool. What map location do you want to explore?” I just randomly picked one, because I don't know. There was like a little bit of a scenario in the beginning, but so much of the game was mechanics that it didn't … you know it's like, “What card you want to play at exactly the right time.”

Patrick Rauland: It's interesting to see when you say that that's for you, you consider at least partially a storytelling game. [crosstalk 00:26:29].

Joseph Limbaugh: Gloomhaven you have to play a few, you have to play it for a while to find the arc. Honestly, I think one of the critics of Gloomhaven is there could be more consequences to the narrative, things that you try to go through. But yeah, it'd be like-

Patrick Rauland: Have you played Pandemic Legacy?

Joseph Limbaugh: I'm not a huge fan of Pandemic. Only because the only times I've played it, one person kind of become like quarterback-

Patrick Rauland: Alpha, yeah, yeah.

Joseph Limbaugh: Yeah. I didn't totally understand, and I'm still trying to understand the rules-

Patrick Rauland: [crosstalk 00:27:12].

Joseph Limbaugh: Yeah, so I just was like, “Just tell me what to do.” You know? That's [inaudible 00:27:16]. But I know it's a good game, because I know people who like it. I respect them.

Patrick Rauland: Yeah, the reason I'm bringing it up right now is I think if you played one game of Pandemic Legacy, it would feel like Pandemic with the rules changed. But if you play all 12 games in the season one or 12 to 24 games in season one, then I bet it feels a little bit more like an arc, because every game basically modifies one thing from the game before, typically. I wonder if … interesting, so yeah, I'm sure there is storytelling, but it requires at least a couple plays for you to get it.

Joseph Limbaugh: Yeah, it's kind of the bare minimum of storytelling, I guess, in some ways. I think most of the storytelling games have little cards you read to kind of add story, or to make the players into game masters, like Arkham Horror. Mansions of Madness now has the app that you use.

Is Game Design Energizing or Exhausting?

Patrick Rauland: Yeah. I think it's a really, really cool cause. I'm sort of on the fence about storytelling games, but if they're done well they're phenomenal. Okay. Does game design in general, when you work on something are you energized? Does it take a lot of energy out of you?

Joseph Limbaugh: Probably, a little from column A, a little from column B. Yeah, I think when I first get an idea, I'm always really excited about it. I don't think this is uncommon, it's like I'm writing stuff down, I'm working on it. Then you get to the part where you're testing, or you get to the part where it's like, “Oh, I have to write this rules out so that they're clear.” Then it's like, “Oh I have to do work now.” Although it still, I think the trick is to kind of keep that excitement going and … I don't know sometimes I actually even writing rules, it's very strange. I'm in the middle of fulfillment for Postcard Dungeons right now. I'm literally, I just took a break from stuffing envelopes to come up here and do this interview.

Joseph Limbaugh: You would think that stuffing envelopes would be a very tedious thing, and it is, but it's also like, “I don't know, I'm so excited that people wanted my game, that I kind of enjoy doing it.” I'm putting the games in the envelopes, I'm like, “These are going to go all over the world to people. Hopefully they will enjoy them.” It's a strange thing. If you're doing something you love, I don't think you ever get completely unenergized, you know what I mean?

How Do You Push Through Low Energy Times?

Patrick Rauland: Yeah. Nothing is like free energy. I'm excited by anything in the world, a music show, or whatever, but it will take some energy to get into it. The reason I ask this question is I think I have an underlying, the underlying question, the question I really want to ask you is how do you get through those … the times where you don't have that much energy? Because there are times where I'm like super jazz, [inaudible 00:30:11] new idea, and I'm writing stuff down in a note card, and then there's other times where people are like, “Hey, change this thing.” You're like, “God, this going to take me two hours to update all the cards.” How do you get through those phases?

Joseph Limbaugh: Yeah. You kind of just have to power through it. It's like exercise. When I first start exercising, I would start, you know, I need to exercise more. At first it's like, “Urgh.” But you have to kind of remember that it's like as you do it for a while, then you actually start to enjoy it, it makes you feel better. I think it's the same thing with this sort of stuff. I'm going to be so … by the time I'm done stuffing these envelopes, my arms are going to ache. I'm going to be sick of it. But I will be so happy that I completed that task. It's the culmination of months and months of work, so I'll be like, “Finally, they're out. They're out in the world.” You have to go, yeah, you have to kind of … you have to get past those. I don't know if there's a good answer other than to power through.

Joseph Limbaugh: I think if people don't go through that stuff, that you end up not succeeding. You have to do some amount of work, even if it's a job you love. Yeah. Even as an actor, there's a lot of … people, I think, see that job and it's like, “Oh, it's super glamorous, and fun and easy.” It's like, “No, it's a horrible grind of going to auditions, and being turned down over and over again.”

Patrick Rauland: Call time, 4:00 a.m.

Joseph Limbaugh: Yeah, yeah.

Patrick Rauland: I used to work in an advertising agency, and I was the web developer. I almost never had to deal with this, then one time I was like, “I want to go out in one of these shoots.” And like, “Call time, 6:00 a.m.” I'm like “Oh. Maybe I'll just edit the website.” I don't want to get up at 6:00 a.m. for work, or be at the office at 6:00 a.m. All right, one more question then the game that you're dreading at the end.

Joseph Limbaugh: [inaudible 00:32:09].

How Many Games Do You Have That Are Unfinished?

Patrick Rauland: How many unpublished, or half-finished games do you have in your brain?

Joseph Limbaugh: I think it's a hard number to get to, but probably somewhere near 100 I would guess. Depends on like if it's something that's just a fragment of a game, if it's something that it's like I've kind of worked out the mechanics to a certain degree, probably less than that, maybe 40 or 50. But definitely, if I'm like, “Oh, I want to make a game that's about cats are fighting monsters” or something, then that's just an idea. I don't have an idea for that game, that game has already been done, I believe, but yeah.

Patrick Rauland: Of the 40, or of the 100 game ideas that you have in your head, what percentage of them are just all D&D characters going into a dungeon? Is there a druids game? Like clerics game?

Joseph Limbaugh: 99%.

Patrick Rauland: Wow, that's impressive.

Joseph Limbaugh: No, I do love dungeon crawls, and I love … I definitely that's influenced … and fantasy worlds. But there's also like science fiction, like the next postcard game I'm working on is a science fiction game sort of like [inaudible 00:33:36], houses fighting each other, political intrigue but with combat sort of thing on postcards. But yeah … yeah, not 90%.

Overrated / Underrated Game

Patrick Rauland: Fair enough. Very cool. All right. I like to end all my chats with a game called Overrated Underrated. Basically I'm going to say a word or phrase, then I'm going to force you to take a position if you think it's overrated or if you think it's underrated. Then maybe like a sentence describing why you think that way. Got it?

Joseph Limbaugh: Okay. Right.

Patrick Rauland: All right. Player elimination in board games, is it overrated or underrated?

Joseph Limbaugh: That's so subjective and personal. I think it's probably underrated, because if you are a good designer, you can make a game that has player elimination, and it won't be as painful, it'll be a fun part of the game. That's what I would say. Yeah, did I play the game right? Did I do it right? Is that how that work?

Patrick Rauland: Yeah, you're doing great. Honestly, I purposely pick out very controversial topic, this is fun to see like which side people land on. Because I think a lot of game designers are [inaudible 00:34:50] with the idea of player elimination. If it's done right, I totally agree with you, if it's done right, it can be amazing.

Joseph Limbaugh: But, it is a design challenge, it's definitely hard to do.

Patrick Rauland: Yes. Because your game is called Postcard Dungeons, I was thinking of things that are underground, here's a weird one. Basements, as in your house, are they overrated or underrated?

Joseph Limbaugh: I feel like the obvious answer is underrated, because they're under the house. I'm so sorry. I would say underrated honestly though, because I think basements have a stigma. Like, “You're living in your parents' basement.” Or basements are where grognards are. But hey, the benefit is basements where grognards are. I spent a lot of time playing role-playing games in my parents' basement when I was a kid, and they're also cooler, it's cooler down there, and not as hot. Yeah. I've had some delightful times in basements. I would say if they're anything, they're underrated. Yeah.

Patrick Rauland: Love it. All right, this one back to games, meeples, are they underrated or overrated?

Joseph Limbaugh: I love meeples. I love them. But I'm going to say they're overrated only because now it's like you can get the craziest … it's like, “Our meeples have … go up to 11.” You know what I mean? “Our meeples make their own meeples, they have meeples inside of them.” It's like, “Hey, I heard you like meeples, so I made meeples with meeples.” I don't know, it's-

Patrick Rauland: Like designer meeples?

Joseph Limbaugh: Yeah, like the super special, fancy meeples to for our games. Once again, though, I look at those I'm like, “I want some of those meeples.” I'm kind of being a hypocrite, and I want those meeples that can hold swords, I want sword-holding meeples, that looks cool. Yeah.

Patrick Rauland: I think I agree with you, but I can't not … I think I agree with you where meeples can maybe be too cool, or maybe they're too highly valued, I don't know how else to say that, too highly valued, but I still … or got, what's the zombie game with the item meeples?

Joseph Limbaugh: It's Tiny Epic Zombies, right?

Patrick Rauland: There we go. I got it, because of meeples stands on a motorcycle.

Joseph Limbaugh: Yes, yeah, totally.

Patrick Rauland: I got it because of the meeple. I'm a victim of my own something. I don't know where I'm going with it, sorry.

Joseph Limbaugh: I have a meeple on my logo for Postcard games. There's a meeple, so I really probably should not be saying they're overrated, right?

Patrick Rauland: I do think it is like the one sort of universal symbol of board games. Because I think D20 is also role-playing games, and I think the meeple is the closest symbol we have for the board gaming community, so I get it. All right, last one. We're recording this before the 4th of July, but it'll come out sometimes after, what do you think of the 4th of July, overrated or underrated?

Joseph Limbaugh: That's a tough one.

Patrick Rauland: Because it's the day you can eat all the food in one day.

Joseph Limbaugh: I've always loved the 4th of July. I love hotdogs, I love all of the cheesy stuff about it too. I love watching fireworks. I think it's probably underrated, I would say. I think it's underrated. Yeah, there's so much contention in the country of America right now that I feel like … it's we can at least come together hopefully and say, “Hey, we fought against depression once.” I don't know. I would say underrated.

Conclusion

Patrick Rauland: Very cool. Joseph, this has been awesome. Thank you for being on the show. Where can people find you?

Joseph Limbaugh: You can find me at PostcardGames.com, or on Twitter, overdroid is my handle. Like over droid, like over a robot. Also, I'm posting riddles there, every day I post a riddle on overdroid, on the Twitter if you're interested in that, if you like riddles. Some of them are good, some of them are not so good.

Patrick Rauland: Awesome. Thank you again. By the way, listeners, if you like this podcast, please leave us a review wherever you listen to podcasts. If you do, Joseph said he'd be willing to send you a selfie from the next dungeon that he enters, whether it be D&D themed or Cthulhu themed.

Joseph Limbaugh: It might just a basement.

Patrick Rauland: Or a really nice basement that are underrated. You can visit the site IndieBoardGameDesigners.com, you can follow me on Twitter, @BFTrick. Thank you all for listening. Until next time, happy designing. Bye bye.